An argument is a list of statements in some natural language (e.g. English) that are either true or false. The final statement is called the conclusion and should follow from the previous statements, called premises.

The above is a description of the non-formal arguments found in philosophy. A formal argument (or proof) is one in which the statements are propositions in a formal language, like FOL or ZFC, and is more prevalent in mathematics. This post will focus on non-formal arguments.

Inference

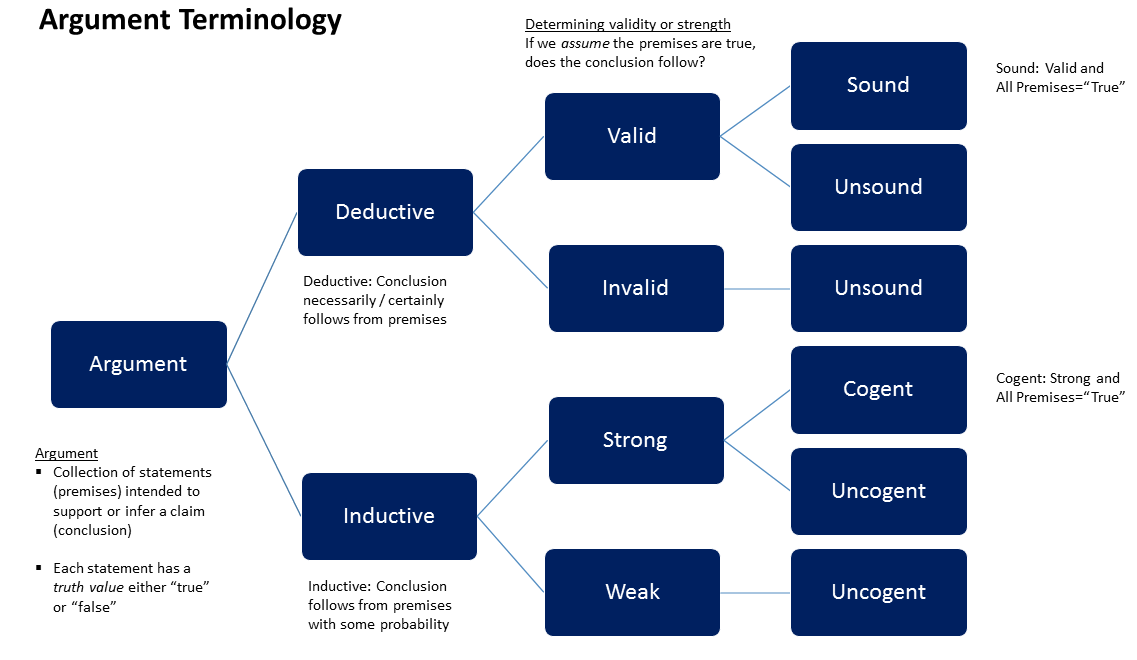

Arguments can employ different types of reasoning, or inferences, to show why the premises imply the conclusion. There are different kinds of systems of inference. Some produce conclusions that are partially uncertain, i.e. only probable, as opposed to being decisive or truth-bearing like other types of inference. The different methods of reasoning used in philosophical arguments can be broadly divided into two types: deductive and inductive.

Deduction

A deductive argument is one that uses logic to show that the premises necessarily imply the conclusion. As opposed to other types of arguments (like inductive and abductive ones) that reason about probable truths, deductive arguments are the only kind that can definitively prove statements. It is no surprise then, that deduction is the prototypical type of inference used in argumentation. The two most vital properties of a deductive argument are its validity and soundness:

Validity

An argument is valid if and only if the truth of its premises logically imply its conclusion. Formally this means the following must hold: $$p_1\wedge p_2\wedge\cdots\wedge p_n\rightarrow q$$ Where $p_1, p_2, \cdots, p_n$ are the premises of the argument and $q$ is its conclusion. If an argument does not satisfy the above it is called invalid and cannot be sound.Soundness

An argument is sound if and only if it is valid and all its premises are true. Formally the latter is: $$p_1\wedge p_2\wedge\cdots\wedge p_n$$ Where $p_1, p_2, \cdots, p_n$ are the argument's premises. Notice that these two conditions are sufficient for us to use the argument form modus ponens: $$\begin{align} (&p_1\wedge p_2\wedge\cdots\wedge p_n)\rightarrow q\\ &p_1\wedge p_2\wedge\cdots\wedge p_n\\ \therefore\ &\hline{q}\\ \end{align}$$ If an argument does not satisfy the above it is called unsound. A good deductive argument is a sound one.Because deductive arguments are based in logic they can be formalized, meaning that they can be reasoned about and verified via totally mechanical means (à la FOL) after being put in a logical form. That said, deductive arguments are different from full on formal proofs in that the atomic statements present in the premises and conclusion are still expressed in a natural language.

Thus, only the validity of a deductive argument can be proved by formalizing it. The truth of the premises, and thus the soundness of the argument, must be established with reasoning and justification (a job fit for induction), unlike a proof whose premises can be proven axiomatically.

This makes the goal of deduction to split up a controversial conclusion into a collection of accepted premises and show that the latter logically implies the former.

Induction

As touched on previously, an inductive argument is one in which the premises should be viewed as supporting evidence in favor of the conclusion, rather than logically implying it.

This evidence based approach means that the conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning can only ever be probable. That said, while inductive arguments may not sound appealing in this light, it is important to note that most real world arguments are based on induction.

The two most important aspects of an inductive argument:

Strength

An inductive argument is said to be strong if the conclusion is probable, when all the premises are assumed to be true. Otherwise, the argument is weak. In this way, strength is analogous to validity in that it only concerns itself with the relationship between the premises and the conclusion.Cogency

An inductive argument is cogent if it is both strong and all its premises are true. Just as before, we can see that this property is analogous to the soundness of a deductive argument, as it is concerned with both the 'correctness' of the argument and the truth of the premises. Where both taken together imply (at least probably) the conclusion.Problem of Induction

Indeed, the whole of science is based on arguments of this nature. For example, after observing in multiple instances that light travels at the same speed in a vacuum, one may inductively draw the conclusion that the speed of light is constant in a vaccum. But one can never be sure that, perhaps the next time they check, the speed of light will actually be different. The same goes for any observation of the physical world. Just because we observe a phenomena over and over again, doesn’t mean it will always occur in the future.

We call this seeming inability to be sure of, or know, anything about the future the problem of induction. Just because all the evidence points to a particular conclusion, there is no logically certain reason to believe the conclusion to be true. Put another way, we cannot deduce anything using observational evidence. Philosophically, this brings into question not just science but all empirical knowledge we claim to have. Just because the sun rose every day of your life, how do you know it will do so again tomorrow? How do you know you can even trust your senses that are telling you the sun rose? They may not have lied to you before, but you could be in some sort of illusion now. And we can go on and on mistrusting everything we have ever known or thought to have known. Indeed, there really is no way out of this problem bar essentially ignoring it.

Chart of Arguments

We can summarize these two types of arguments and their ‘correctness’ via the following chart:

Extracting Arguments

Arguments in real life, and even in academic discourse/papers, aren’t usually given as a numbered list of premises. Instead they are given implicitly as a, hopefully, coherent paragraph or passage of reasoning.

As a result, before we can analyze an argument for its validity or strength, we must first extract it from the passage. This is not a concrete process and some liberty must be taken to represent what the author might have implicitly meant to be in their argument. Premises added by interpretation to keep the argument valid are called suppressed premises.

Staying true to the source is paramount in a historical analysis of the ideas of past philosophers, however, when engaging in a debate with another, it is good practice to assume the strongest version of your interlocutor’s argument rather than go through the formality of disproving them on a technicality or easily remedied premise. We call this charitable interpretation, and abiding by it produces more productive and interesting debates.

Which method of Inference?

When told to extract an argument by a philosophy professor without being told what type of inference should be used, deduction is common. However when analyzing an argument in the sciences, especially the social sciences, the argument is most likely inductive.

Similarly, when extracting arguments subconsciously as we do in everyday life, we are most likely using inductive reasoning. This is because most people don’t express/form their opinions, thoughts, and ideas in a fully logical manner. Not only would this be limiting from an evolutionary perspective, as it would severely limit the conclusions we could confidently make, we technically couldn’t form any conclusions due to the problem of induction.