Definition

The Cartesian product $\times$ is an operation on two sets, call them $A$ and $B$, that returns the set of all ordered pairs with their first element from $A$ and their second from $B$. Formally, we can think of it as shorthand for the following:

\[A\times B=\{(a,b)\mid a\in A \land b\in B\}\]Existence in ZFC

Utilizing the Kuratowski definition of ordered pairs, we can show that the Cartesian product of two sets can be constructed from the axioms of ZFC. In particular, it is a subset of the following easily constructed set:

\[A\times B \subseteq \mathcal{P}\left(\mathcal{P}\left(A\cup B\right)\right)\]Proof

First, note that $A\cup B$ is guaranteed by the axiom of union and that its power set is guaranteed by the axiom of power set. Next notice that, among many other elements, the power set of $A\cup B$ contains: $$\{a\},\{a,b\}\in\mathcal{P}\left(A\cup B\right)$$ where $a$ and $b$ are elements in $A$ and $B$ respectively. Now if we take the power set again we'll see that the result contains, among other things, the elements: $$\{\{a\},\{a,b\}\}\in\mathcal{P}\left(\mathcal{P}\left(A\cup B\right)\right)$$ for all $a$ and $b$ in $A$ and $B$. Now invoke the axiom of subset to choose only those elements that fit the description and we are done!$n$-ary Cartesian Product

It is easy to see how one might generalize this notion to $n$ sets. For example, by chaining the Cartesian product twice we are left with a set of $3$-tuples:

\[\begin{align*}(S_1\times S_2)\times S_3&=\{(\left(s_1,s_2),s_3\right)\mid\forall i\in[1..3],\ s_i\in S_i)\}\\ &=\{\left(s_1,s_2,s_3\right)\mid\forall i\in[1..3],\ s_i\in S_i)\} \end{align*}\]Repeating this $n$ times, we are left with the following for any $n$ sets:

\[S_1\times S_2\times \cdots \times S_n=\{\left(s_1,\cdots,s_n\right)\mid\forall i\in[1..n],\ s_i\in S_i)\}\]The resulting product has an arity of $n$ and is dubbed an $n$-ary Cartesian product. We can denote product of multiple sets more concisely via the following notation:

\[\prod_{i=1}^nS_i=S_1\times S_2\times \cdots \times S_n\]Notice that the parenthesis are omitted. This is because the cartesian product is left-associative, a property that is expounded upon further below.

Simultaneity of Arity

Recall that any $n$-tuple can be simultaneously interpreted as a $k$-tuple where $1\le k\le n$. Likewise, this means that an $n$-ary Cartesian product:

\[\prod_{i=1}^nS_i=S_1\times S_2\times \cdots \times S_n\]can also be interpreted as having arity $k$. We can show this by first defining a new indexed set:

\[U_i = \begin{cases} \displaystyle \prod^{n-k+1}_{i=1}S_i & i=1 \\ \displaystyle S_{n-k+i} & i>1 \end{cases}\]And now we can phrase the original $n$-ary product as a product of $k$ sets:

\[\prod_{i=1}^kU_i=\left(\prod^{n-k+1}_{i=1}S_i\right)\times S_{n-k+2}\times \cdots \times S_n\]Indexed & Infinitary Products

It is possible to extend the notion of the Cartesian product to allow for the product of any indexed family of sets:

\[\prod_{i\in I}S_i=\{f:I\to\bigcup_{i\in I}S_i\mid \forall i,f(i)\in S_i\}\]In words, this Cartesian product returns every function that takes an element $i\in I$ and maps it to an element $f(i)\in S_i$. Note that this allows for index sets with an infinite cardinality, leading to infinitary Cartesian products:

\[\underbrace{\text{binary},\text{trinary},\cdots,n\text{-ary}}_{\text{finitary}},\cdots;\underbrace{\aleph_0\text{-ary},\aleph_1\text{-ary},\cdots}_{\text{infinitary}}\]Note that this generalizes the first definition because $n$ can be thought of as a set with $n$ elements as per its construction as a natural number (i.e. $n=[0..n-1]$), and so we can take it to be our index set $I$. As a result, these two definitions are isomorphic for finitary products.

Useful Shorthand

Note that the normal finitary product produces a set of tuples while this indexed product produces a set of functions. This distinction is important because the definition of a function depends on that finitary product.

And so the indexed product is more a useful shorthand for denoting the set of all functions from some $I$ to some set of domains $S_i$, rather than a replacement of the finitary product.

Special Products

Below are a list of special cases of the Cartesian product:

Cartesian Powers

When dealing with the repeated Cartesian product of a single set $S$, we call it the $n$th Cartesian power and use the following notation: $$S^n=\prod_{i=1}^nS=\underbrace{S\times S \times \cdots \times S}_{n\text{ sets}}$$ Using the indexed definition of Cartesian product we can denote the Cartesian power, i.e. set of all functions from $I$ to $S$, like so: $$S^I=\prod_{i\in I}S=\{f\mid f:I\to S\}$$Empty Set

A special case of the Cartesian product is when one of the factors $S_j=\emptyset$. When this happens the entire product 'collapses' into the empty set. This is because there are simply no elements in $\emptyset$ to be mapped to by $f(j)$. We can state this as the following for any $n$-ary/indexed product: $$(\exists j\in I)\ S_j=\emptyset\implies\begin{cases} \displaystyle\prod_{i=1}^nS_i=\emptyset,&n\text{-ary product}\\ \displaystyle\prod_{i\in I}^{\phantom{n}}S_i=\emptyset,&\text{Indexed product} \end{cases}$$ Indeed this absorbing property of the empty set is the only case in which a Cartesian product could result in the empty set.Unary Product

Because our product notation allows us to denote the cartesian product of any indexed family of sets, it is natural for us to ask what is returned when the family consists of a single set. The answer is just that set itself. Consider $\{S_1\}$: $$\prod_{i=1}^1S_i=\prod_{i\in\{1\}}S_i=S_1$$We define the unary product in this way to make our product notation more convenient (e.g. recursive definition of product has a base case of 1 set). It also matches up with our convention of $1$-tuples simply being elements of a set, as mentioned in the $n$-tuples post.

Nullary Product

Another special case is the product of 0 sets, that is, a product with index set $I=\emptyset$. This is called an empty or nullary Cartesian product. The index set being empty means that there can only be one function (the empty function) in the product: $$\prod_\emptyset=\{f_\emptyset:\emptyset\to\emptyset\}=\{(\emptyset,\emptyset)\}$$ Recall that we define a function as an ordered pair of a cartesian product and a subset of that product. In this case both are $\emptyset$.Properties

Note that the following properties refer to the standard binary Cartesian product and not its indexed variant.

Positional Properties

Left-Associative

When faced with an $n$-ary Cartesian product without parenthesis, it is conventionally evaluated from left to right. That is to say the Cartesian product is left-associative: $$A\times B \times C=(A \times B)\times C$$ This convention intuitively meshes with the definition of $n$-ary Cartesian products and $n$-tuples, i.e. $((a,b),c)=(a,b,c)$.Non-Commutative

The Cartesian product is a non-commutative operator: $$A\times B \not= B \times A$$ This should be obvious as the ordered tuples $(a,b)\not=(b,a)$ where $a\in A$ and $b\in B$ via the definition of tuple equality.Non-Associative

The Cartesian product is a non-associative operator: $$\left(A\times B\right) \times C \not= A\times \left(B \times C\right)$$ Similar to its non-commutativity, we can illustrate this by noting that $((a,b),c)\not= (a,(b,c))$ where $a\in A$, $b\in B$, and $c\in C$.Distributive Properties

\[\begin{align*} A\times\left(B\cup C\right)&=\left(A\times B\right)\cup \left(A\times C\right)\\ A\times\left(B\cap C\right)&=\left(A\times B\right)\cap \left(A\times C\right)\\ \left(A\times B\right)\cap \left(C\times D\right)&=\left(A\cap B\right)\times \left(C\cap D\right)\\ A\times\left(B\setminus C\right)&=\left(A\times B\right)\setminus \left(A\times C\right)\\ B\subseteq C&\leftrightarrow\left(A\times B\right)\subseteq \left(A\times C\right)\\ \left(A\times B\right)\subseteq \left(C\times D\right)&\leftrightarrow\left(A\subseteq B\right)\land \left(C\subseteq D\right)\\ \end{align*}\]If $A$ and $B$ are members of some universal set $U$, then their absolute complement is denoted $A^C$ and $B^C$ respectively.

\[\left(A\times B\right)^C=\left(A^C\times B^C\right)\cup\left(A^C\times B\right)\cup\left(A\times B^C\right)\]Cartesian Factorization

The Cartesian product is analogous to the integer product we are familiar with in the following way: a Cartesian product can be ‘factored’ into its component sets. Even further, there exists a unique prime factorization of any Cartesian product that recovers its original sets.

Finitary Product

To find the $i$th Cartesian Factor (CF) of an $n$-ary Cartesian product $P$ we simply have to find the union of the $i$th index of all tuples in $P$:

\[\operatorname{CF}_i^n(P)=\bigcup_{p\in P}\{\pi^n_i(p)\}=S_i\]Where $\pi^n_i(p)$ is the tuple extraction function.

Indexed Product

In the more general case where our Cartesian product $P$ is of an indexed family $\{S_i\} _{i\in I}$ then we can find the $i$th factor in the following way:

\[\operatorname{CF}_i(P)=\bigcup_{p\in P}\{p(i)\}=S_i\]Note that we can recover the index set $I$ from the product $P$ by simply choosing any one of its elements (a function, i.e. an ordered pair) and extracting its first element. This will be the Cartesian product of its domain $I$ and codomain. We can then finally extract $I$ from this binary product as described in the finitary case. This is all to say:

\[\left(\forall p\in P\right)\, \operatorname{CF}_1^2(\pi_1(p))=I\]Also note that, unlike the finitary case, indexed products can only be interpreted one way and so only have one factorization.

Prime Factorization

The Cartesian prime factorization (CPF) is simply the indexed set of all the Cartesian factors. Note that the indexing is important because, unlike integer factors, the order matters. And so for an $n$-ary Cartesian product $\prod_{i=1}^nS_i=P$ we can say:

\[\operatorname{CPF}^n(P)=(\operatorname{CF}_i^n(P))_{i=0}^n=(S_i)_{i=1}^n\]Note that due to the simultaneity of arity, the factorization of a finite product depends on what arity we consider to it be. We can resolve this if we specify that the unique prime factorization of a finitary product requires it be considered the maximum arity possible.

For an indexed Cartesian product $\prod_{i\in I}S_i=P$ we can say:

\[\operatorname{CPF}(P)=(\operatorname{CF}_i(P))_{i\in I}=(S_i)_{i\in I}\]Factorization of the Empty Set

Analogous to the number zero, the empty set $\emptyset$ does not have a unique prime factorization. That is because if one of the factors of a Cartesian product happens to be the empty set, then the result too will be empty and thus there is no way to recover the original factors from it. In other words, any family of sets can serve as a factorization of $\emptyset$ so long as one of them is $\emptyset$ itself.

Examples & Uses

Relations

An $n$-ary relation is defined as an ordered pair with the first element being an $n$-ary Cartesian product and the second a subset of that product. For example, $\le$ is a binary relation on the set $\mathbb R$:

\[\begin{gather} \le\,\,\equiv\,(\mathbb R\times\mathbb R,G)\\ G\subseteq\mathbb R\times\mathbb R \end{gather}\]This allows us to formalize statements like $4\le7$ as the set membership $(4,7)\in G$.

Cardinal Multiplication

Cartesian products are used to define the product of two cardinal numbers:

\[\left|X\times Y\right|=\left|X\right|\left|Y\right|\]And in general for any indexed family of cardinal numbers:

\[\left|\prod_{i\in I}X_i\right|=\prod_{i\in I}\left|X_i\right|\]Where the left product denotes the Cartesian product while the right denotes the cardinal product.

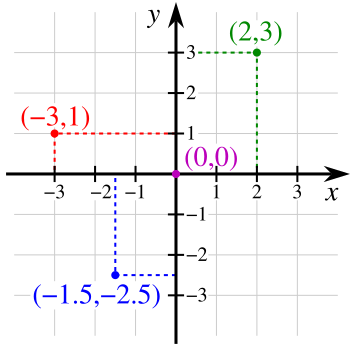

Cartesian Coordinates

Every point in $2$-space represents an element of the Cartesian product of the Reals with itself, i.e. $\mathbb{R}^2$. This can be generalized to $n$-space with every point being an element of $\mathbb{R}^n$:

\[\mathbb{R}^n=\{(x_1,x_2,\cdots,x_n)\mid (\forall i\in [1..n])\, x_i\in\mathbb{R}\}\]

Points in $3$-space are necessary in describing the position of objects and particles in space and thus set up the study of motion, the causes of that motion, and ultimately the rest of physics.

Moreover $2$-space, and less frequently $3$-space, is used in plotting and making inferences from data as well as visualizing functions over an interval of numbers. We can even consider an infinite dimensional real space $\mathbb R^\mathbb \omega$, aka the set of all real sequences.