What is FileToPNG?

FileToPNG is a tool I wrote in Java that converts the raw binary representation of any file into a corresponding PNG image representation. The resulting PNG (being a lossless file type) can be sent through text, email, etc. before finally being reconstructed back into its original form.

The project’s GitHub repository can be found here.

While FileToPNG’s main purpose was to be a tool that allowed for the sending of files over image only communication channels, I’ve found that, based on what type of files are put into it, the resulting images show some interesting patterns. I will elaborate on a couple of these findings in this post.

The Main Algorithm

While I have programmed a primitive UI (the code for which can be found here) to make using the tool easier, it’s not the main focus of FileToPNG and is really just boilerplate Java.

The real meat of the program is the conversion functions for PNG to File and vice versa. The code for this can be found here

The algorithm goes something like this:

- Convert the file into a string of bytes (8 bits = 1 byte).

- Read through this list and make a pixel out of every 3 bytes. This can be done because a pixel is comprised of 3 colors (red, green, and blue) each with a value from 0-255. These 256 values can be represented in 8 bits (because 28=256).

- Once a list of pixels (which should be about 1/3 of the size of the byte list) has been made, create a square image (in .png format) out of these pixels.

- Account for files whose bytes aren’t a multiple of 3. (I used special ‘2 byte’ and ‘1 byte’ pixels that have different alpha values to demarcate them)

Reconstructing the images into files is as simple as reversing this process.

Side Note on Function Mapping

You can think of the program as an injective function that maps the set of all finite bit strings $\{0,1\}^+$ to the set of all square images. It’s injective because every bitstring results in a unique image, allowing us to reverse the transformation.

Because this image is a square of pixels with 4 layers (red, green, blue, and alpha), we can denote the set of images as the set of all rank 3 tensors with size $n\times n\times 4$ and integer elements from $0$ to $255$1. Putting this together, our program can be thought of as the following function:

\[\text{FileToPNG}:\{0,1\}^+\to \left(\mathbb{N}_{255}\right)^{n\times n\times 4}\]Side Note on Exclusion of Alpha Channel

You may notice that while .png files have 4 color channels (red, green, blue and alpha), I only use 3 to store the data of the file and leave the alpha channel to indicate whether a given pixel only holds 1 or 2 bytes of information rather than 3.

This is obviously inefficient and I’m sure there are better ways of representing the file as a png while simultaneously taking advantage of all 4 channels, effectively saving 25% more space for each pixel. One way to do this might have to do with the dimensions of the image. There is no reason for the image to be a square.

I haven’t done anything about this because, in its current state, the algorithm is better suited to exploring the representations of the data it encodes rather than efficiently compressing them in image form. Having the alpha channel available would make the resulting images (and information they represent) harder to visualize.

Properties of PNG Representations

FileToPNG doesn’t do any sort of encrypting or compression of the file’s data. As such, the PNG representation it spits out can give us an unfiltered look at the file’s structure.

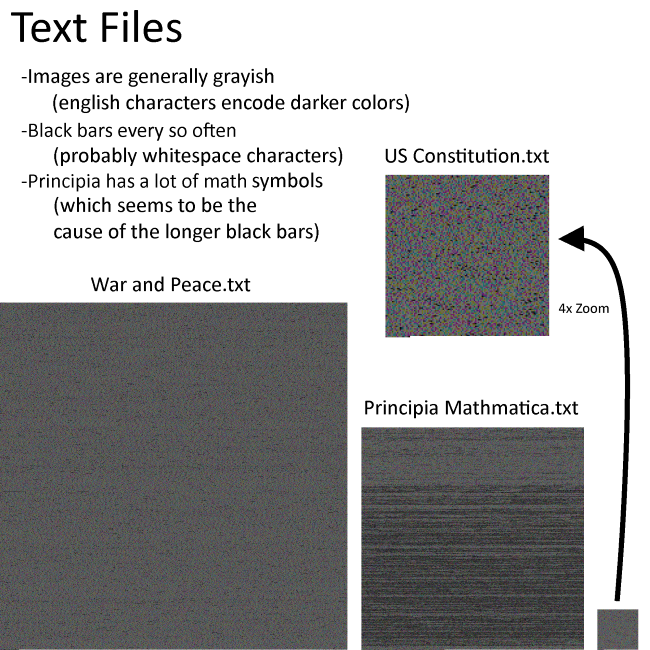

Text Files

Take text files for example. Their content, of course, varies widely depending on the length and topic of discussion. But, even if they don’t use the same language, they all still use the same set of Unicode characters which all have the same configuration of bits. Meaning they share some similarities:

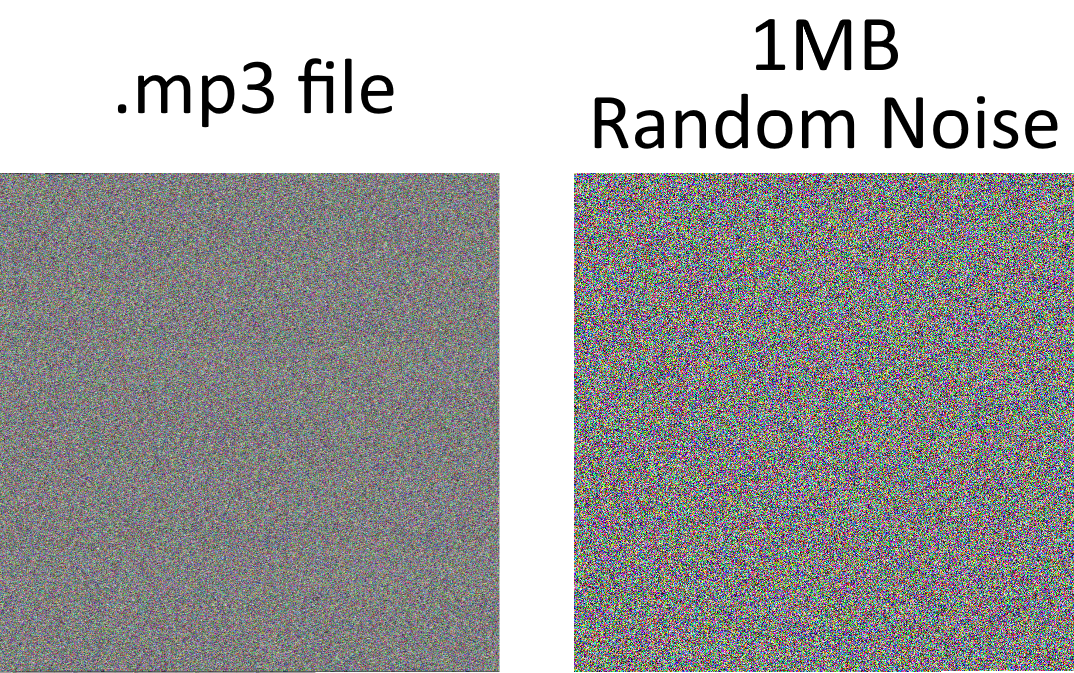

Music Files

This one was kind of surprising. When I took an .mp3 file of a song and put it through the program, the resulting image was seemingly random:

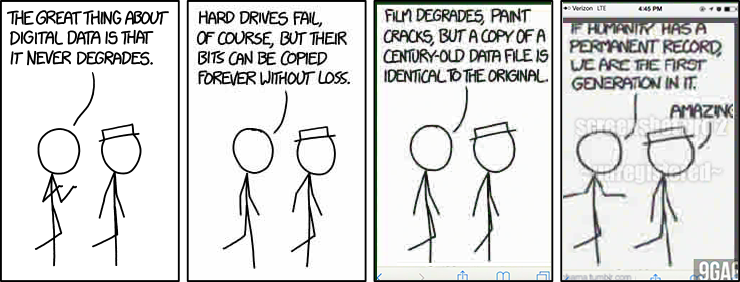

I was disappointed at first, but then I realized that randomness is fundamentally information packed. That is to say, if the PNG representation had some sort of overarching structure, then that would imply that there is still some redundancy in the file that could be compressed, thereby making the file smaller and more random looking.

This lines up with the fact that mp3 files are lossy (i.e they sacrifice perfect quality for a smaller size).

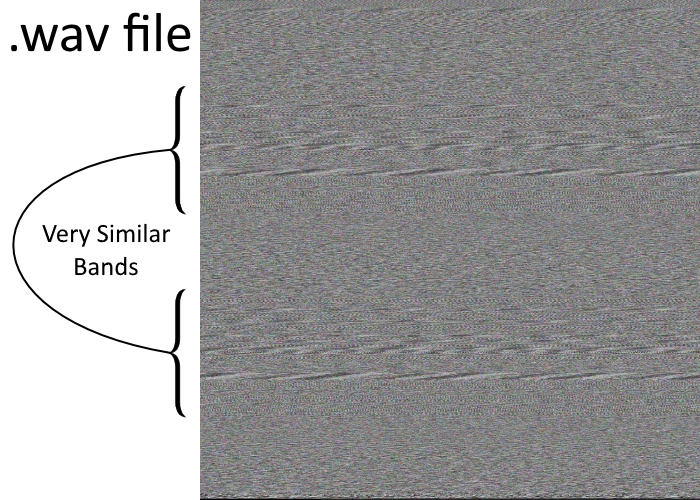

The natural step forward at that point was to get a .wav version of the song, which is lossless, and see if it had any structure. And, as expected, it did:

Note the repeating bands of different ‘frequencies.’ The image was also much bigger in area due to being lossless (the true image isn’t shown here as an act of mercy to your browser).

It is in this way that we can examine how “densely packed” with information a given file is. If we see patterns in the colors or structure of the image, we know there can be more compression done. However, if the image is indistinguishable from random noise, then it’s probably rich in information. This qualitative measure of information is a useful tool in analyzing images converted with FileToPNG.

Nintendo 64 ROMs

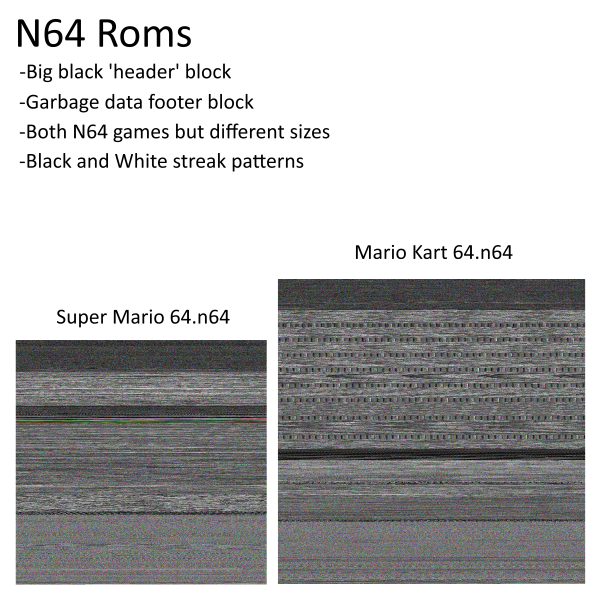

As a final test, I thought I would try converting a couple of Nintendo 64 games (in file form) that were on my desktop to PNGs and, unsurprisingly, they share many similarities:

Interested, I did some research into N64 cartridges and found out that all ‘ROM dumps’ (files that were created by copying a physical N64 cartridge onto a computer) have what’s called a header. This header includes custodial information like the game’s version, internal name, and other bits of information that might be interesting to a game historian. These headers are the black boxes at the top of Super Mario 64 and Mario Kart 64 respectively.

You may also notice that the Super Mario 64 rom is smaller than the Mario Kart 64 one, implying that it has a smaller file size. Apparently, N64 games came on a variety of hardware with different storage capacities and capabilities. This may seem normal nowadays but in an era where all games had to work on the same piece of limited hardware, this variability is pretty amazing.

Another similarity can be spotted after the last black bar, at the bottom of the images. Past this point, both ROMs consist of ‘garbage data’ meant to fill up the game cartridge they were stored on. You can tell because this section looks more like random noise then the rest of the picture.

-

Remember an image in its raw form is just a matrix of pixels, a bitmap, where each pixel is represented by a red, blue, green, and alpha value from 0 to 255, i.e. 4 bytes. The alpha represents how transparent the pixel is. This only applies to image formats like PNG that support tranparency. ↩