Poorly Defined Concepts

What is jealousy? What is a cat? What does it mean to be free? What are you?

These aren’t foreign questions to us. Jealousy is an emotion we feel when we envy someone for what they have, a cat is an animal with a tail and four paws, freedom is the state of being able to do what you please, and I am a human being with thoughts and emotions.

But what is jealousy really? What’s a cat really? What does it really mean to be human?

There is no formal definition of these concepts. We just know them when we see them. I know what jealousy feels like, I know what being human feels like (I hope), and I know a cat when I see it.

“Alright,” you might say, “maybe humanity and jealousy are too lofty to state objectively, but can’t cats be formally defined? Surely a cat has a particular genome that defines it regardless of its outward appearance, right?”

But in a world where cats evolved from another species via gradual mutations to individual base pairs in their DNA (not big leaps), where do we draw the line between cat and cave-cat, so to speak?

Moreover, is a picture of a cat a cat? It certainly represents the notion of a cat, but it doesn’t exactly have genetic material. Plus, there is no formal way to tell whether a given picture is of a cat or not. No formula, no physical law of cats. We can tell a cat, real or drawn, from another animal using our intuition, whatever that is.

“But it’s easy” you might say, “just look for a tail, 4 legs, pointy ears and some fur.” What about hairless cats? a cat drawn with no tail? a cat who’s ears are down, etc. There are so many exceptions that it’s a miracle we are even able to tell cat from houseplant!

What’s Wrong with being Poorly Defined?

Why is this a problem? Well, without a concrete definition, the statements we can make about a concept are limited and just as hazy as the definition.

Take morality. Unlike a well defined concept, you can’t point to some mathematical construction or set of rules that it follows. I can’t tell you without a doubt whether a given action was ‘moral’ or not, nor can I even define morality.

Killing is certainly immoral… right? Well, except when it’s in the defense of yourself or others. What about hitting a kid as punishment? We certainly wouldn’t find that acceptable today, but it was commonplace not too long ago. How can there be an objective definition of morality if it is riddled with exceptions and even evolves over time?

A chemist can give you certainty that a particular solution will erode a metal because chemistry is a formal science with mathematical definitions of all its concepts. A psychologist, however, may only have a hazy idea of why you may feel a certain emotion (whatever an emotion is) and what could have caused it.1

Computation

Computers are a prime example of this, as they can only deal with problems that are well defined (i.e programmable via a set of steps or algorithm). Ask it to solve the quadratic function, model an atom, or even play music and it’ll do just fine. But ask it to judge how strong an argumentative essay is and it might run into trouble. Digital music is just a sound wave sampled at a high rate, easy. But what is a good essay, formally speaking?2

Well Defined Concepts

To formally deal with any idea or concept, it has to be well defined. By making our definitions more concrete we can make more precise statements about these ideas. This is the stage in which math and science can take place.

Take the atom. An atom is a collection of protons, neutrons, and electrons which are further composed of elementary particles, all of which are governed by an exact set of equations3. A Cesium atom, for example, is thus completely mathematically defined. Everything about it is encapsulated in it’s wave function4, no need to look at the natural world to understand it.

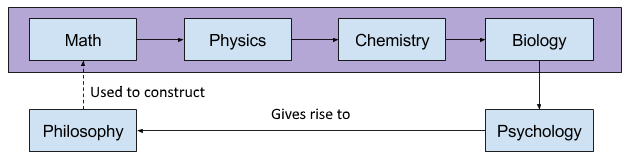

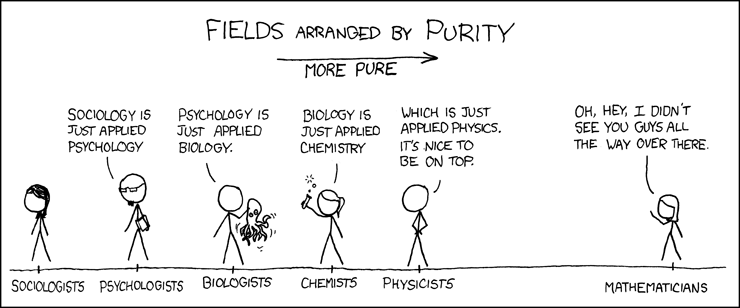

Note that this applies to all atoms, and thus all molecules (since they are made of atoms), and further anything in the universe made of matter, like humans.5 That we can express all things in the universe in terms of equations shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, we know that math is the bedrock of science and thus of formal knowledge as a whole:

Take psychology. It is, in a gross oversimplification, just applied biology. Likewise biology is just applied chemistry, which is just applied physics, which is just (as we’ve seen) applied mathematics. This chain of abstraction applies to all fields of human knowledge6, but its relation to psychology and the human mind will be particularly useful to us…

Bridging the Gap

Now consider the concept of love. It seems impossible to define it objectively right? Sure it’s an evolutionary aid to sexual reproduction, but that’s far from concrete and certainly ignores our own experience of it.

- We must first ask ourselves “what is love?”

- Well it’s an emotion, right?

- Sure, but what’s an emotion?

- A state of mind.

- But what is “the mind”?

- Well, the mind arises from the brain processing the information blasted into it via our senses.

- What is the brain made up of, and what comprises its state?

- The brain is comprised of trillions of specialized cells called neurons. These neurons connect to form large neural networks and communicate via electrical activity and chemicals known as neurotransmitters.

And further, neurons are comprised of different organelle and so on until we reach atoms and ultimately the fundamental particles of the universe.

This relation between the most fundamental (and very well defined) concepts in our universe, like elementary particles, to the most hazy and abstract ones, like emotions, is what will allow us the bridge the between poorly defined and well defined in a somewhat, admittedly, crude way.

Brain Graphs

Consider the human brain. It is simply a collection of interconnected neurons, no? We can represent that neural network as graph. This graph will contain a bunch (billions) of nodes, each representing a neuron, and even more (trillions) of edges between those nodes, representing connections.

Making our definition a bit more concrete, we can define any brain, in a single instant, as a graph of it’s neurons:

\[B=\left(N,C\right)\]- \(B\) is a graph of a brain.

- \(N\) is the set of all nodes in \(B\) (neurons).7

- \(C\) is the set of all connections between members of \(N\) (neurons).8

Functions of Time

Of course, a thought doesn’t occur in an instant, it happens over a small interval of time. So these brain graphs would actually be brain graph functions over time. Plugging in a time into the function would output the state of the brain graph at that moment in time.

We can formalize this via:

\[B(t)=\left(N,C(t)\right)\]- \(B(t)\) is a function of the graph of a brain over time.

- \(N\) is the same as before (assuming the neurons in the brain stay constant during this thought)

- \(C\) is the function of the set of all connections between members of $N$ (neurons) over time.

Set of all of Brain Graph Functions

Finally we can define an idea or concept as the set \(S\) of all the possible brain graph functions that (we would consider) are thinking of that idea:

\[S=\left\{B \in T\mid B \text{ is a brain that is thinking of S}\right\}\]- \(S\) is a particular idea (represented by a set).

- \(B\) is a brain graph function. (The $(t)$ is omitted because we are just talking about the function itself).

- \(T\) is the set of all possible brain graph functions.

Notice that in this definition we are quantifying over all possible brain graphs not just the ones that have existed or will exist. Thus, for example, a cat would be defined as:

\[\begin{align*} \text{Cat}&=\left\{B \in T\mid B \text{ is a brain that is thinking of cat}\right\}\\ &=\left\{B_1,B_2,B_3,B_4,\cdots\right\} \end{align*}\]In the example above \(B_1, B_2, B_3\) and so on are all different possible human brains that are thinking about cats.

How does this Definition even Help?

Remember when I said formally defining concepts allows us to make formal statements about them? Well that was only partially true. While this “set of all possible particle configurations” definition is more formal than your standard notion of, say, jealousy, it’s not exactly helpful in trying to understand the nature of emotion of people’s interactions with each other.

So then what’s the real point? The real point is purely a semantic one. A scientist/philosopher might like to associate some physical meaning to ideas like emotion or creativity. Thus, we can assure ourselves that everything imaginable can be considered physical (and further mathematical) in some sense. Even if that physicality is purely expressed as your brain thinking about said concept, it’s still just particles following the same physical laws.

It also serves as a sort of refutation of the idea that some “things” are “nonphysical”. Many philsophers like to point to, for example, shadows as things that aren’t physical (they are just the lack of photons) yet are still existant (who would say shadows aren’t “real”?). But what these philosophers miss is that shadows are just an idea in our heads, and ideas are physical.

An Aside

The idea I presented above is, of course, ridiculous and riddled with problems. It is just meant to serve as a rough idea of how one might formalize the notion of an “idea” or “concept” when, at first, it may seem that they can only exist in our minds. Indeed these concepts do only exist in our minds, but our minds are purely physical, unless you obstinately claim the contrary.

One such problem I would like to somewhat address is the apparent circularity of saying “the notion of cat is encompassed by the set of all brains that are thinking of the concept of cat.” This isn’t as bad as it sounds because it should really be phrased as “the notion of cat is encompassed by the set of all brains that are thinking of what the brain considers the concept of cat.” This definition draws on our own subjective ideas of cats to objectively define them. That is to say, we can take advantage of the human brain’s unique capacity to introspect to help us define these concepts.

Another problem is that a certain concept or idea that occurs in a human mind may not be isolated in their brains. The human mind is a complex mechanism whose function is a product of one’s body, senses, and general environment. This problem can be solved by simply replacing the idea of brain graph with the set of cells that represent the human body or even set of particles/wavefunction that comprise that human body if necessary. The brain graph formulation I used above is simply for intuitive convenience.

-

That said, it’s not too far-fetched to imagine an operational definition of emotions based on the amount of certain neurotransmitters in one’s brain. But of course, this is a bit of an oversimplification. ↩

-

This problem of doing shakily defined tasks on computers can be partially dealt with via machine learning. And the underlying philosophy behind it’s effectiveness in the real world is called the manifold hypothesis. ↩

-

We call that set of equations the standard model of particle physics. Of course, our model of physics is still incomplete as it does not adequately marry gravity to quantum mechanics. ↩

-

A wave equation is simply a quantum mechanical description of matter. ↩

-

Of course, modeling even large molecules (much less humans) as quantum wave functions is pretty much out of our reach computationally. As such, the claim that quantum wave functions can model all aspects of our lives is solely a theoretical one. ↩

-

That said, if we wanted to organize all fields of study onto a single chart, the chain of abstraction would be more like a web of abstraction… ↩

-

Note that since neurons are not all the same (different size, different type, etc.), way may wish to have a definition that can account for these differences for different neurons \(n\) in the set \(N\) ↩

-

Like with each neuron being different, each connection is different (i.e. different weightings), and so we might model this as a weighted graph of some sort (at least as a first approximation). ↩