$\renewcommand{\vec}[1]{\mathbf{#1}}$

Kinematics describes the motion of objects through space over time. That is to say, it allows us to predict the future and past trajectories of objects in terms of their position, velocity, and acceleration. How an object gets it’s acceleration (i.e. forces) is what dynamics seeks to explain.

In this post we will be discussing translational kinematics in relation to classical mechanics, where space and time are separate and position is definite. Indeed, when it comes to both relativistic and quantum physics, the very notion of quantities like position and velocity are put into question. The resulting kinematics under these regimes are beyond the scope of this post.

Variable Acceleration

To calculate the motion of an object with continuous acceleration over time, simply refer to the definitions of velocity and acceleration:

\[\begin{align} \vec{v}&=\frac{d\vec{x}}{dt}\\ \vec{a}&=\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt} \end{align}\]Integrating these equations we get:

\[\begin{align} \vec{x}&=\int\vec{v} \,dt+\vec{x}_0\\ \vec{v}&=\int\vec{a} \,dt+\vec{v}_0 \end{align}\]- $\vec{x}$ is the object’s position as a function of time.

- $\vec{x}_0$ is the initial position, usually taken to be at \(t=0\).

- $\vec{v}$ is the object’s velocity as a function of time.

- $\vec{v}_0$ is the initial velocity, usually taken to be at \(t=0\).

- $\vec{a}$ is the object’s acceleration as a function of time.

- $t$ is time.

Constant Acceleration

When acceleration is assumed to be constant, as is the case for any physical system not subject to a net force, the following kinematic equations can be derived:

Position Independent Equation

$$\begin{align} \vec{v}&=\int\vec{a} \,dt+\vec{v}_0 &\text{(integral def. of $\vec{v}$)}\\ &=\vec{a}\int dt+\vec{v}_0 &\text{($\vec{a}$ is constant)}\\ &=t\vec{a}+\vec{v}_0 \end{align}$$

$$\boxed{\vec{v}=\vec{v}_0+t\vec{a}}$$

Velocity Independent Equation

$$\begin{align} \vec{v}&=t\vec{a}+\vec{v}_0 &\text{($\vec{x}$ independent Eq.)}\\ \vec{x}&=\int\vec{v} \,dt+\vec{x}_0 &\text{(integral def. of $\vec{x}$)}\\ &=\int(t\vec{a}+\vec{v}_0) \,dt+\vec{x}_0&\text{(plug in $\vec v$)}\\ &=\int t\vec{a}\,dt + \int\vec{v}_0 \,dt+\vec{x}_0 \\ &=\vec{a}\int t \,dt + t\vec{v}_0+\vec{x}_0 &\text{($\vec{a}$ is constant)}\\ &=\frac{t^2\vec{a}}{2}+t\vec{v}_0+\vec{x}_0 \end{align}$$

$$\boxed{\vec{x}=\vec{x}_0+t\vec{v}_0+\frac{t^2\vec{a}}{2}}$$

Acceleration Independent Equation

$$\begin{align} \vec{v}&=t\vec{a}+\vec{v}_0 &\text{($\vec{x}$ independent Eq.)}\\ \vec{a}&=\frac{\vec{v}-\vec v_0}{t}&\text{(solve for $\vec a$)}\\ \vec{x}&=\frac{t^2\vec{a}}{2}+t\vec{v}_0+\vec{x}_0 &\text{($\vec{v}$ independent Eq.)}\\ &=\frac{t^2\frac{\vec{v}-\vec v_0}{t}}{2}+t\vec{v}_0+\vec{x}_0&\text{(plug in $\vec a$)}\\ &=t\frac{\vec v_0+\vec{v}}{2}+\vec{x}_0 \end{align}$$

$$\boxed{\vec{x}=\vec{x}_0+t\frac{\vec v_0+\vec{v}}{2}}$$

Time Independent Equation

$$\begin{align} \vec{v}&=t\vec{a}+\vec{v}_0 &\text{($\vec{x}$ independent Eq.)}\\ {\vec{a}}t&=\vec{v}-\vec{v}_0&\text{(rearrange)}\\ \vec{x}&=t\frac{\vec v_0+\vec{v}}{2}+\vec{x}_0 &\text{($\vec{a}$ independent Eq.)}\\ 2(\vec{x}-\vec{x}_0)&=t(\vec{v}+\vec{v}_0)&\text{(rearrange)}\\ 2\vec{a}\cdot(\vec{x}-\vec{x}_0)&=t\vec{a}\cdot (\vec{v}+\vec{v}_0)&\text{(dot product w/ $\vec a$)}\\ &=(\vec{v}-\vec{v}_0)\cdot(\vec{v}+\vec{v}_0)&\text{(plug in $t\vec a$)}\\ &=\vec{v} \cdot \vec{v} - \vec{v}_0 \cdot \vec{v}_0 &\text{(foil dot product)}\\ &=\left \| \vec{v} \right \|^2-\left \| \vec{v}_0 \right \|^2\\ \end{align}$$

$$\boxed{\left \| \vec{v} \right \|^2 = 2\vec{a}\cdot(\vec{x}-\vec{x}_0)+\left \| \vec{v}_0 \right \|^2}$$

Notational Cleanup

There are a couple of things we can do to clean up this set of 4 equations before we display them all together.

Displacement vs. Position

While these equations describe the movement of an object in terms of its initial and current position, $\vec{x}_0$ and $\vec{x}$ respectively, it is common to think about kinematics in terms of displacement, or change in distance, $\Delta\vec{x}$ instead:

\[\Delta\vec{x}=\vec{x}-\vec{x}_0\]Average Velocity

If we look at the acceleration independent equation, we can see it contains the expression $\frac{\vec v_0+\vec{v}}{2}$. As it turns out, when acceleration is constant, this expression is actually equivalent to the object’s average velocity $\overline{\vec{v}}$:

Derivation

$$\begin{align} \overline{\vec{v}}&=\frac{\vec{x}-\vec{x}_0}{t} &\text{(def. of $\overline{\vec{v}}$)}\\ t\overline{\vec{v}}&=\vec{x}-\vec{x}_0\\ \vec{x}-\vec{x}_0&=\frac{t^2\vec{a}}{2}+t\vec{v}_0 &\text{($\vec{v}$ independent Eq.)}\\ t\overline{\vec{v}}&=\frac{t^2\vec{a}}{2}+t\vec{v}_0\\ \overline{\vec{v}}&=\frac{t\vec{a}}{2}+\vec{v}_0\\ \vec{v}&=t\vec{a}+\vec{v}_0 &\text{($\vec{x}$ independent Eq.)}\\ t\vec{a}&=\vec{v}-\vec{v}_0\\ \overline{\vec{v}}&=\frac{\vec{v}-\vec{v}_0}{2}+\vec{v}_0=\frac{\vec v_0+\vec{v}}{2} \end{align}$$

Dot Product

When deriving the time independent kinematic equation, we used the dot product when manipulating the expressions $t\vec{a}\cdot(\vec{v}+\vec{v}_0)$ and $(\vec{v}-\vec{v}_0)\cdot(\vec{v}+\vec{v}_0)$. We were justified in doing so because the dot product is both commutative and distributive.

The dot product of a vector with itself is that vector’s squared norm and is often denoted as such:

\[\vec{v}\cdot\vec{v}=\left \| \vec{v} \right \|^2=v^2\]The Kinematic Equations

Taking into account average velocity, the simpler dot product notation, and using displacement instead of position, we can rewrite the kinematic equations for constant acceleration as:

\[\begin{gather} &\vec{v}=\vec{v}_0+t\vec{a} &\text{($\vec{x}$ independent)}\\ &\Delta\vec{x}=t\vec{v}_0+\frac{t^2\vec{a}}{2} &\text{($\vec{v}$ independent)}\\ &\Delta\vec{x}=t\overline{\vec{v}}=t\frac{\vec v_0+\vec{v}}{2} &\text{($\vec{a}$ independent)}\\ &v^2 = v_0^2+2\vec{a}\cdot\Delta\vec{x} &\text{(t independent)} \end{gather}\]Graphing

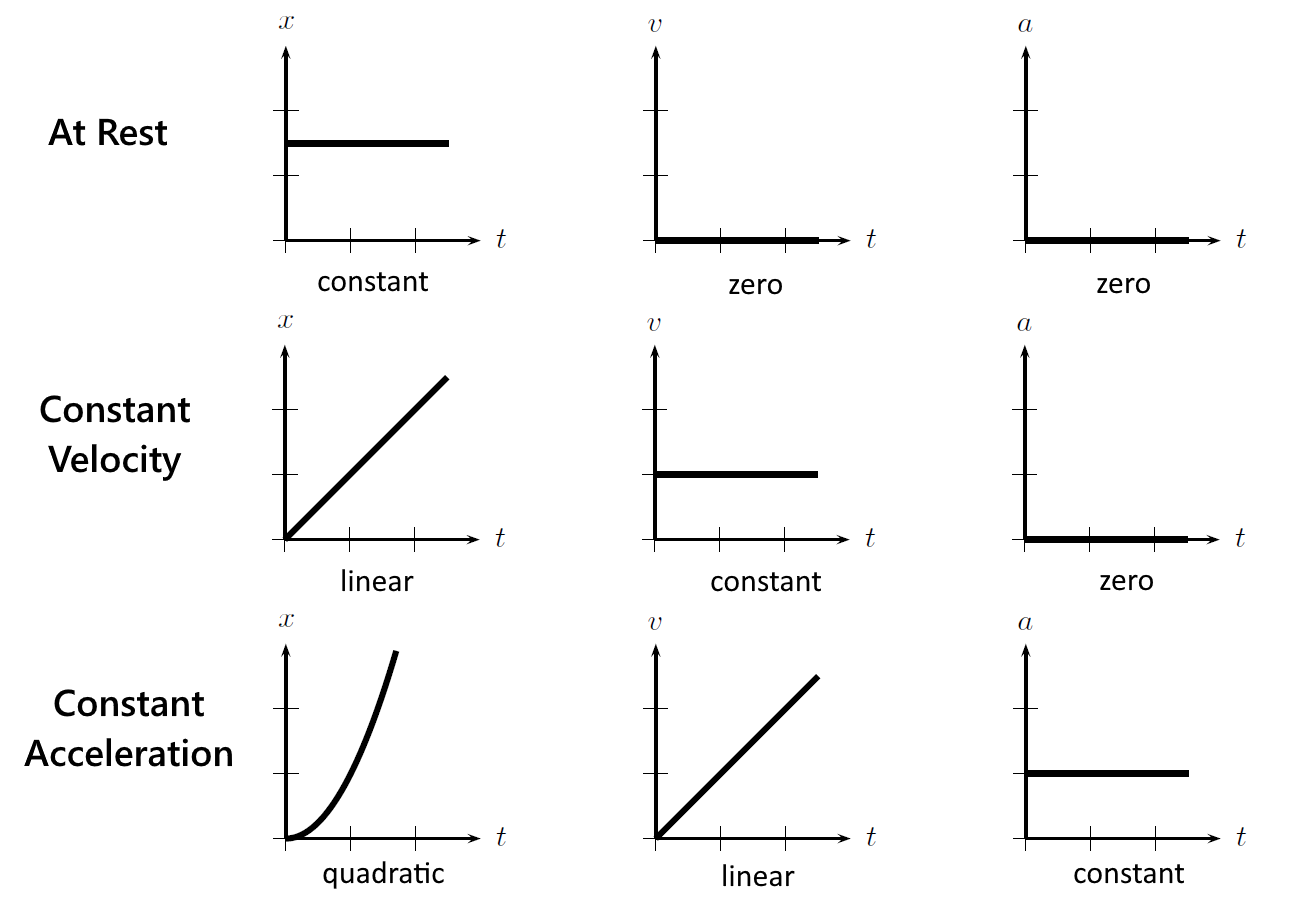

When the position, velocity, and acceleration functions are graphed with respect to time, their graphs are related by the kinematic equations.

General Info

For any graph of $\vec{x}(t)$

- Slope of the secant line created by two points is the average velocity during that time interval.

- Slope of line tangent to curve at time \(t\) is the object’s instantaneous velocity at $t$.

For any graph of $\vec{v}(t)$

- Slope of the secant line created by two points is the average acceleration during that time interval.

- Slope of line tangent to curve at time \(t\) is the object’s instantaneous acceleration at \(t\).

- Area under a region of the curve from $[a,b]$ is the object’s displacement during $[a,b]$.

For any graph of $\vec{a}(t)$

- Area under a region of the curve from $[a,b]$ is the object’s change in velocity during $[a,b]$.

Graph Shapes